Project overview

The United Kingdom is estimated to lose 1.5 million years of healthy life to diet-related illness, disease, and premature death each year (1).

The retail food environment plays an influential role in influencing consumers’ diets, with most of the UK populace carrying out their grocery shopping in large supermarket retail chains (2). In recognition of this, studies have been conducted to examine various methods in which consumers can be nudged towards healthier and more sustainable choices at the point of purchase. One way to do this is by running swap interventions, where the trial participants are encouraged to select a healthier alternative to the option in their baskets. However, many swap intervention trials have been set in online experimental supermarkets (3-7) which were noted to have higher swap acceptance rates than when the intervention was carried out in a real-life setting (8).

This project aimed to investigate if in-store signposting would be able to nudge customers to make a healthier swap between two comparable products, across eight product pairs.

Data and methods

The trial occurred countrywide in February 2021 and focused on eight product pairs, consisting of an original product and a ‘healthier’ alternative across the following categories: cereal, cheese, chicken, coleslaw, fries, granola, rice, and tuna. The trial products were selected to ensure that they offered a ‘healthier’ nutritional profile in that they contained lower (or equal) levels of the ‘less healthy’ nutrients such as saturated fat or sugar and higher (or equal) levels of the ‘healthier’ nutrients e.g., dietary fibre.

| Product category | Original product | Healthier swap |

| 1. Fries | Curly fries | Crinkle cut fries |

| 2. Chicken | Chicken Kiev | Breaded chicken |

| 3. Cereals | Frosted Flakes | Honey Loops |

| 4. Tuna | Tuna in Sunflower Oil | Tuna in Spring Water |

| 5. Rice | Long grain white rice | Long grain brown rice |

| 6. Granola | Fruit and nut granola | Low sugar granola |

| 7. Cheese | Grated cheddar | Light grated cheddar |

| 8. Coleslaw | Creamy coleslaw | Reduced fat coleslaw |

Figure 1: A table showing the original product and the healthier swap offered within the same category

For the trial data, we received basket-level sales for a 12-week pre-intervention period, a 4-week trial period and a 12-week post-trial period. We also received data for the same period for 2018/2019 and 2019/2020 to get a better understanding of usual purchasing trends in the absence of the trial. We analysed data from two regions in the north and south of the UK determined by the retailer’s distribution areas.

Figure 2: An example of the wobblers used in store. The wobblers were designed to sit on shelf and protrude out to attract attention.

This wobbler shows the original product, the creamy coleslaw and its healthier alternative, the reduced fat coleslaw with a message encouraging customers to swap for the reduced fat coleslaw as it has 330 less calories per pot.

Our approach to analysing this data was to use interrupted time-series analysis to predict the sales in the trial period if the trial had not taken place (our counterfactual). The absolute and relative effects were then calculated by comparing the predicted value to the actual sales, with effectiveness determined at the 95% significance level.

We also conducted an Eatwell analysis on the baskets to track how well the baskets are aligned with the Eatwell guide (the UK diet recommendation), and whether this changed because of the trial. To achieve this, products were matched to segments of the Eatwell guide using a text matching algorithm (9) that was altered to better fit the retailer.

Key findings

During the analysis, the success of the trial was defined as seeing an increase in the sales of the healthier swap, and no change or a decrease in sales of the unhealthier swap when compared to predicted sales based on previous purchasing behaviour.

During the trial period, the sales of the healthier swap for the cereals (32.37%) and coleslaw (71.47%) increased significantly, while sales of the original product remained stable. These products had messaging on sugar and calorie reduction respectively, which have been found to be high on shoppers’ health priorities (10) . Therefore, it could be hypothesised that the messaging resonated more with the customers.

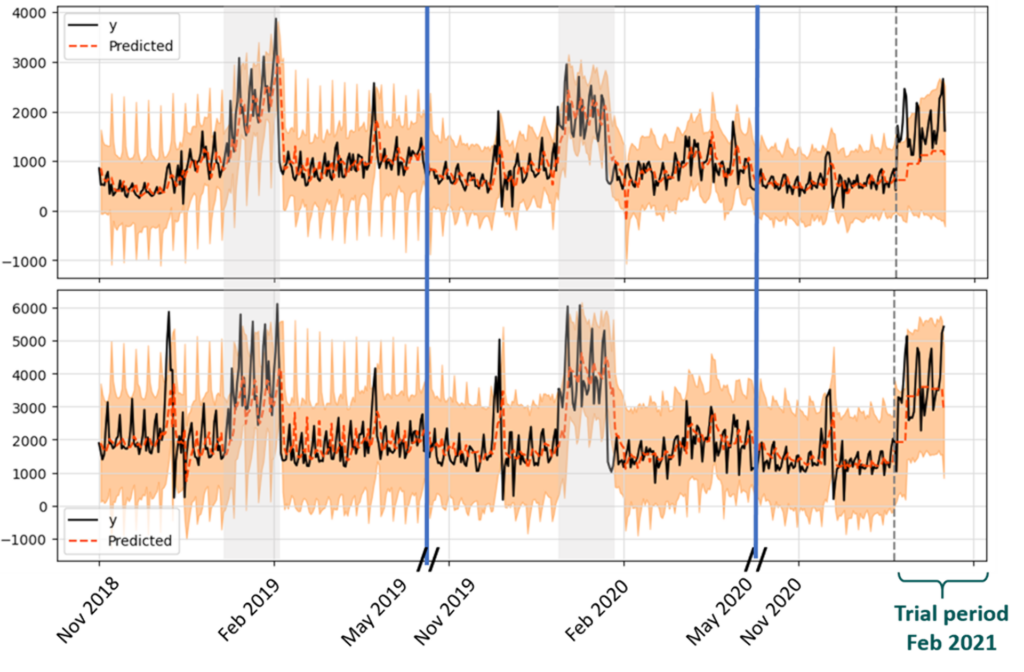

Figure 3: Two interrupted time series analysis graphs showing the predicted results for the reduced fat coleslaw (top) versus the original product coleslaw (bottom).

The grey bands indicate the matched trial period in the previous two years, while the blue line indicates the time gap between the post-trial periods and the pre-trial periods. The orange dotted lines show the predicted sales by the model, while the solid black line shows the actual sales of the two coleslaw products. The actual sales for the reduced fat coleslaw (top graph) are significantly higher than the predicted sales during the trial period.

For fries, rice and cheese, the sales of both the healthier and the original product increased during the trial. This implies that the signposting acted as a cross promotion and brought attention to both products, thus leading to an increase in sales. This could be problematic if it means that customers purchase a higher number of calories overall as a result of the signposting bringing attention to a product they had not considered purchasing and influencing them to buy the product. The messaging for these three products focused on fat (fries and cheese) and fibre (rice) which shoppers report as less important, according to survey data (10). Interestingly, despite increased sales in both variants, there was a greater increase in the sales for the healthier swap (90.71%) when compared to the original product (32.58%) for fries. This might mark fries in general as an easy entry point to encourage people to try a healthier version as they would assume that since the product is still a bag of potato fries, the taste would not be affected – making the jump easier.

Lastly, for the chicken, tuna and granola, the trial had no impact on the sales of the healthier product. Shoppers might be more resistant to swaps offered in protein-based meal centres like meat and fish which typically have a higher price point, as suggested by a study by Forwood et al. on online swaps (3). For the granola, the sales of the original product were higher than predicted, suggesting the trial had unintended consequences of encouraging customers to buy the less healthy variant. This could be because fibre messaging is associated with a negative trade-off with flavour (11), furthermore the healthier granola was a relatively new product and may not yet have been fully adopted by the customers.

Value of the research

This research shows that signposting can be used to nudge customers to make healthier choices by offering swaps which provide a more manageable option for people who wish to eat healthier but do not know where to start. However, differences in success by product type suggest more work is needed to unpick customer motivations and identify suitable categories and messages to encourage swaps. The type of nutrient targeted in the messaging plays a larger role in influencing the customer as it was observed that sugar and calorie messaging were more successful in the trial in comparison with the fat and fibre messaging.

Quote from project partner

“When developing this trial, we wanted to understand how best to help our customers make healthier choices at point of sale, where we know they make decisions.

This trial has demonstrated the importance of product choice and types of messaging used. Going forward, we plan to continue testing what works around signposting, in collaboration with University of Leeds and IGD, to help customers eat healthier.”

- LIDL, GB

Insights

- Signposting can be used to promote healthy swaps.

- Signposting could lead to cross-promotion.

- Clear messaging is essential to prevent unintended consequences.

People

Rayan Onyonka, Leeds Institute for Data Analytics

Victoria Jenneson, School of Medicine, and Leeds Institute for Data Analytics

Michelle Morris, School of Medicine, and Leeds Institute for Data Analytics

William Young, School of Earth and Environment and Leeds Institute for Data Analytics

Partners

Institute of Grocery Distribution

LIDL GB

Funders

Funded by Institute of Grocery Distribution with support from the Consumer Data Research Centre.

References

1. National Food Strategy. National Food Strategy. 2021.

2. Department for Envirnoment Food & Rural Affairs. Food statistics in your pocket. [Online]. 2023. [Accessed 10/03/2023]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/food-statistics-pocketbook/food-statistics-in-your-pocket#uk-grocery-market-shares-12-weeks-ending-on-4th-september-2022chart15

3. Forwood, S.E., Ahern, A.L., Marteau, T.M. and Jebb, S.A. Offering within-category food swaps to reduce energy density of food purchases: a study using an experimental online supermarket. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015, 12, p.85.

4. Koutoukidis, D.A., Jebb, S.A., Ordonez-Mena, J.M., Noreik, M., Tsiountsioura, M., Kennedy, S., Payne-Riches, S., Aveyard, P. and Piernas, C. Prominent positioning and food swaps are effective interventions to reduce the saturated fat content of the shopping basket in an experimental online supermarket: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019, 16(1), p.50.

5. Payne Riches, S., Aveyard, P., Piernas, C., Rayner, M. and Jebb, S.A. Optimising swaps to reduce the salt content of food purchases in a virtual online supermarket: A randomised controlled trial. Appetite. 2019, 133, pp.378-386.

6. Bunten, A., Porter, L., Sanders, J.G., Sallis, A., Payne Riches, S., Van Schaik, P., Gonzalez-Iraizoz, M., Chadborn, T. and Forwood, S. A randomised experiment of health, cost and social norm message frames to encourage acceptance of swaps in a simulation online supermarket. PLoS One. 2021, 16(2), p.e0246455.

7. Jansen, L., van Kleef, E. and Van Loo, E.J. The use of food swaps to encourage healthier online food choices: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021, 18(1), p.156.

8. Stuber, J.M., Lakerveld, J., Kievitsbosch, L.W., Mackenbach, J.D. and Beulens, J.W.J. Nudging customers towards healthier food and beverage purchases in a real-life online supermarket: a multi-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2022, 20(1), p.10.

9. Potin, F. FrancescaPontin/Eatwell_product_classification: Version 1.0. Zenodo. 2022.

10. Institute of Grocery Distribution. IGD ShopperVista research. October 2022.

11. Raghunathan, R., Naylor, R.W. and Hoyer, W.D. The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition and Its Effects on Taste Inferences, Enjoyment, and Choice of Food Products. Journal of Marketing. 2006, 70(4), pp.170-184.